|

alligatorzine | zine |

|||

|

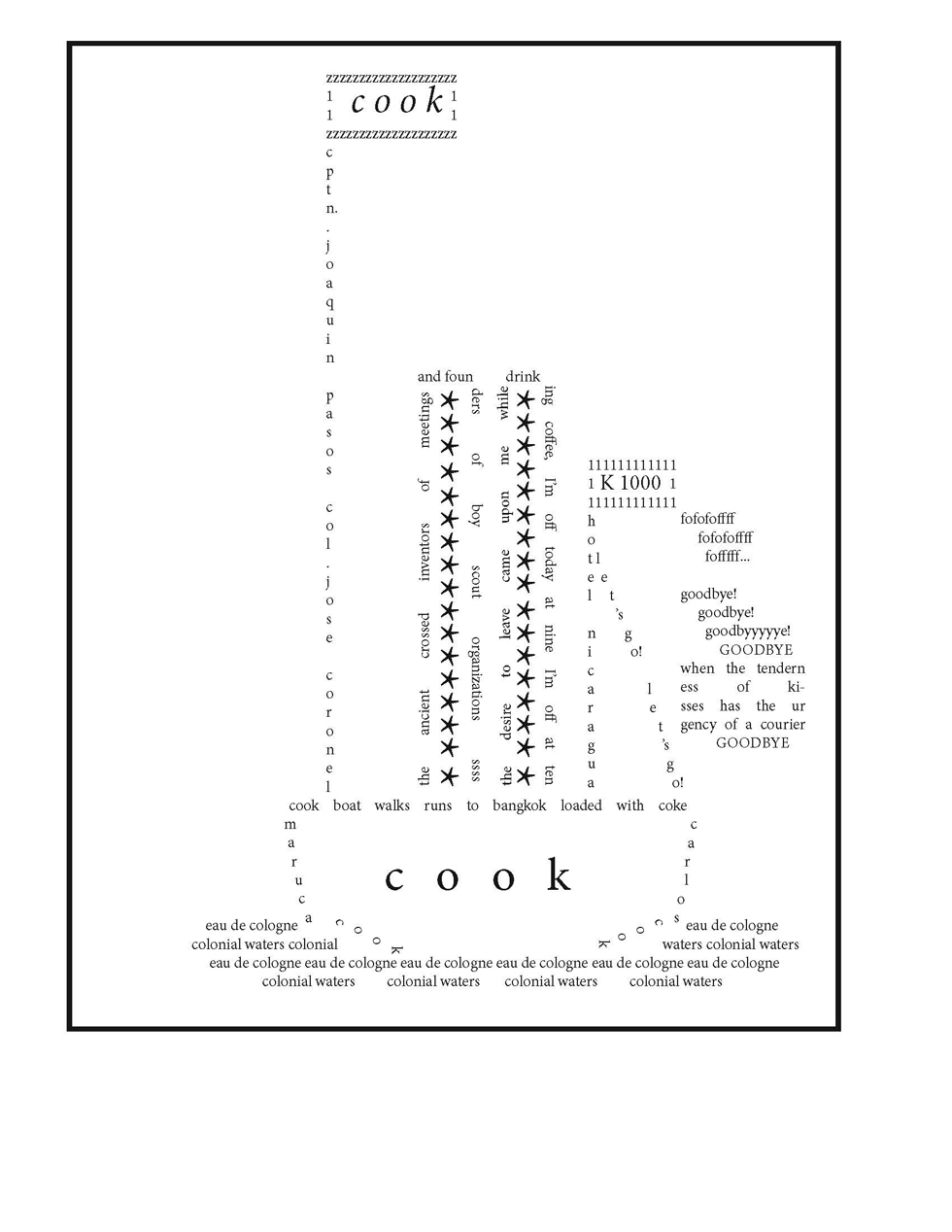

Nicaragua’s Vanguardia, considered one of the first avant-garde movements in Latin America, got its start with José Coronel Urtecho’s composition of “Ode to Rubén Darío,” a clever skewering of the patron bard’s poeticized language, written in 1926 and first published in ’27. The group, which initially consisted of Coronel Urtecho, Pablo Antonio Cuadra, and Joaquín Pasos, embraced a nativist aesthetic, but their work drew on a vast range of new influences, from anthropology and psychoanalysis to cinema and contemporary European literature. In 1927, Coronel Urtecho returned from a three-year spell in San Francisco, where he had translated North American poets including Whitman, Pound, Moore, and Eliot, whose influence is evident in much of Vanguardia’s verse. In 1930, the movement formally established the Anti-Academy, which was opposed to any “spurious, bewitched, and sterile” manifestation of the past. It is impossible not to see a political stance in this aesthetic orientation. In the words of Ernesto Cardenal, “Nicaragua produced two important things during [the 1930s], the Vanguardia and Sandino. A single spirit animated both movements, and in some sense the two were one and the same.”

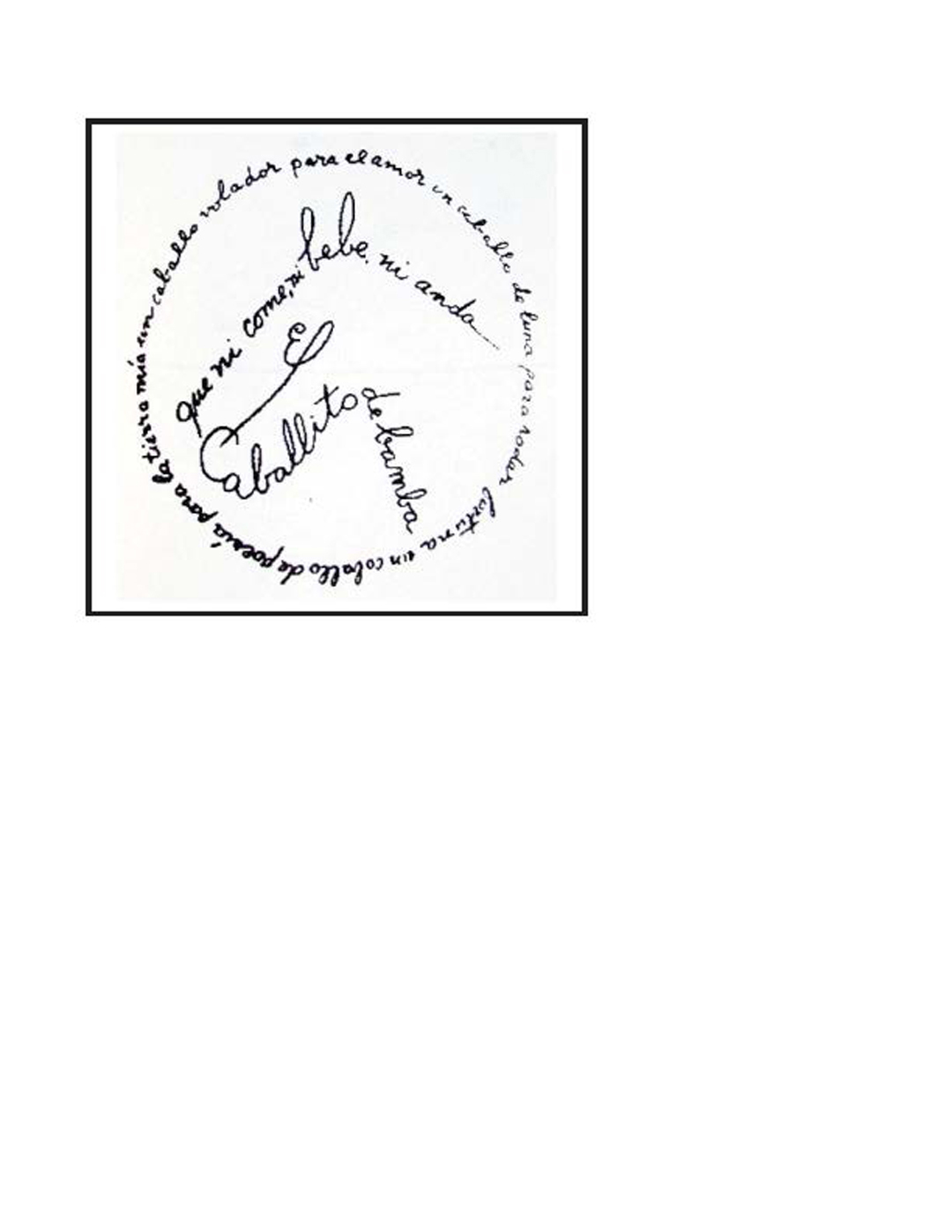

This calligram reflects the Vanguardia’s reverence for and rediscovery of folk and oral poetries, as well as their rootedness in the historical Spanish-language literature they sought both to defy, revitalize, and transcend. The phrase “caballito de bamba,” not at all common today, alludes to traditional Spanish comedies and picaresque novels. The lines “ni anda ni come ni bebe, / como el caballo de bamba,” which Cuadra here reorders, is how Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600 – 81), considered to have initiated the second cycle of Spanish Golden Age theatre, refers to a character stupidly in love. The term has also been used to refer to those considered useless and stupid, and appears, in a variation that features the horse andando without ever eating or drinking, in La vida y hechos de Estebanillo González, hombre de buen humor [The life and facts of Estebanillo González, man of good humor] (1646).

The form and playfulness of “Caballito de bamba” also suggests the influence of the Mexican orientalist and experimentalist José Juan Tablada’s handwritten calligrams in Li-Po y otros poemas (1920), a landmark in Latin American literature for its fusion and Americanization of both Eastern and European literatures; given that book’s limited print run in Caracas, Venezuela, it is likely that the similarities are mere coincidence, but the Vanguardia’s enthusiasm for collecting books from abroad was boundless, and it is probable that its members knew of Tablada by reputation at least. |

José Coronel Urtecho was a poet, translator, and critic who, having spent three years in the United States, introduced the work of Eliot, Poe, Pound, and Whitman to his Vanguardia peers. |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||

|

Masterpiece, by José Coronel Urtecho |

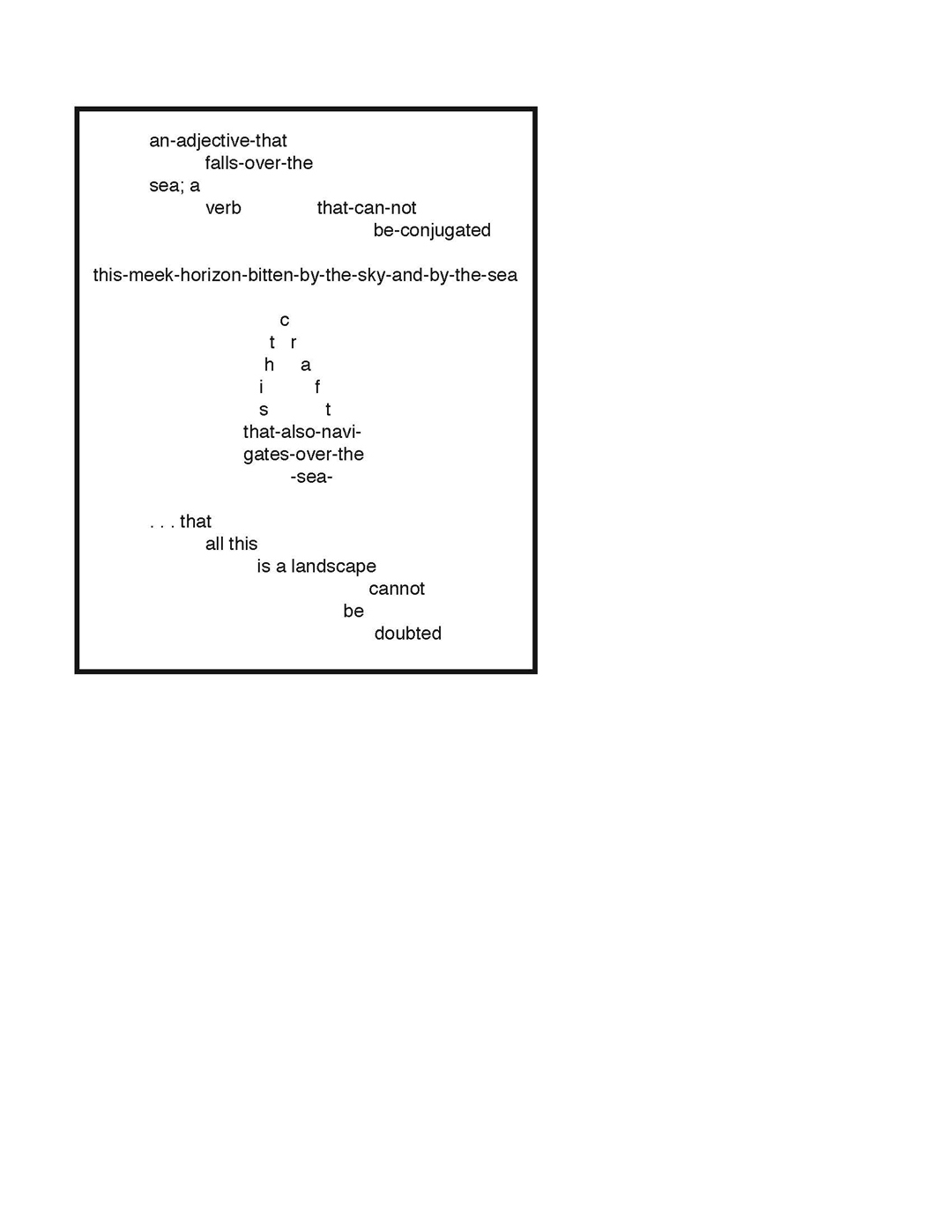

Impertinent Landscape, by Pablo Antonio Cuadra |

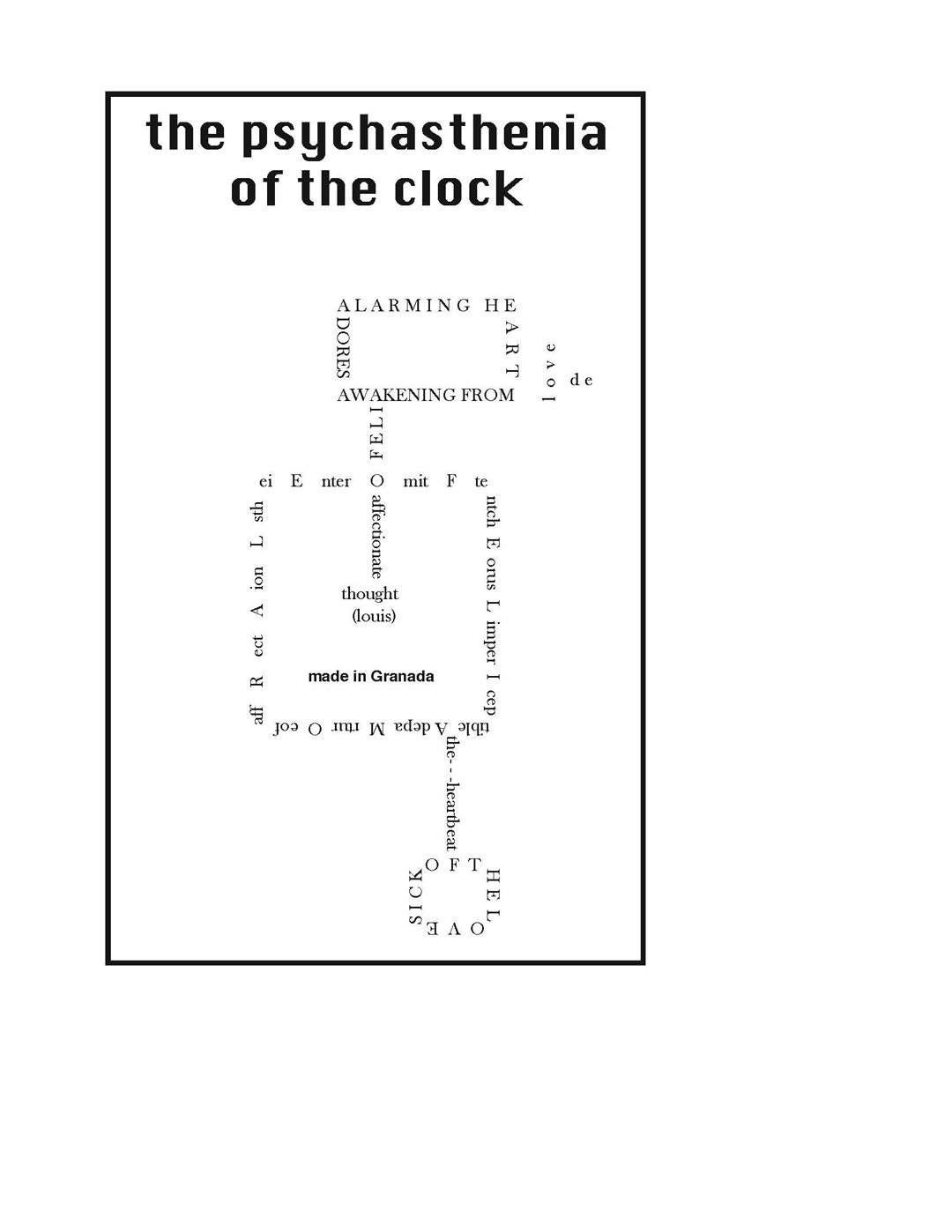

The Psychasthenia of the Clock, by Luis Downing Urtecho |

Windmill of Fear, by Octavio Rocha |

Caballito de Bamba, by Pablo Antonio Cuadra |

Cook Boat, by Joaquín Pasos |

||||||||